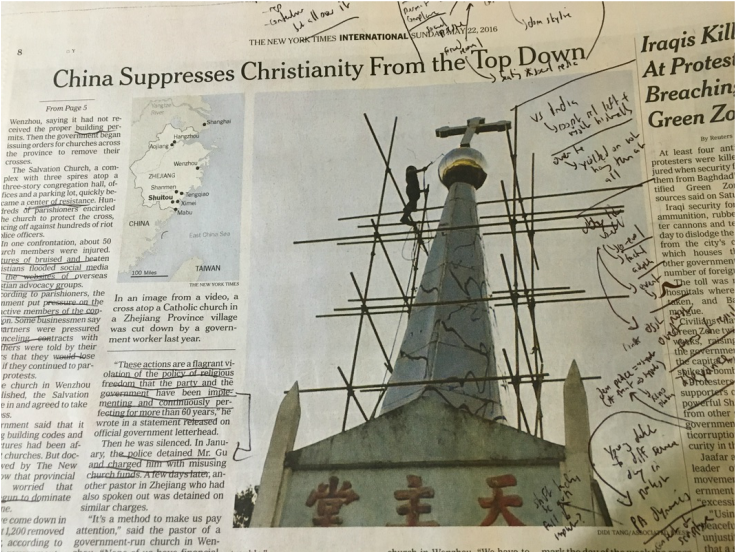

On its merits, the piece ("China Suppresses Christianity From the Top Down" by Ian Johnson) had some good points and directly seemed to be relevant to the scholarship that has developed over the last 50 years. It was addressing a topic that has long been covered by social scientists: the repression of citizens. The new(ish) twist, it considered the repressive action of the Chinese government against those who were attempting to practice Christianity. Recently the subject of repression within China has been the subject of some recent attention within political science. The piece highlighted the contentious/dramatic removal of crosses from churches while also noting the use of other tactics from heavy-handed protest policing to softer activities such as the forcing compliance with building ordinances that were seldom enforced. The piece noted the puzzling aftereffect that some repression seemed to prompt resistance not compliance/acquiescence. The piece noted that the government employed a rhetorical justification whereby outsiders/foreigners were blamed for instigating trouble.

All this should sound familiar to those following the repression literature because it should be. The point is simple: had the author of the article consulted the literature, they would have been guided to a clearer as well as slightly different and i will maintain better article.

For example, had the author consulted the literature, they would have discussed the fact that repression and anti-state mobilization are co-evolutionary phenomenon. As one actor develops a tactic such as removing crosses or putting crosses up (which in the context of China challenged both the state's official position against religion [acknowledged within the piece] but also the state's official position against capitalism [not acknowledged by the piece]). The co-evolutionary perspective would have been useful for it would have taken the snapshot (the event[s]) of interest to the article and put it into a broader historical context that is essential for understanding what is going on - something akin to a "conflict cycle". Indeed, one wonders from the article where the cross removal fits within the broader conflict cycle. Are we at the beginning of a new age, the middle, the radical flank aftermath? No clue is offered.

Had the author consulted the literature, they would have discussed the fact that the more overt manifestation of Chinese repression (a word that is not once used in the article mind you) is generally a tactic used when governments either don't know who to go after or when they want to send a very clear message to an audience about what is/is not acceptable. The latter clearly appears to be the case in the article. That said, the author notes that there is also the simultaneous use of permitting, false criminalization as well as a measure of "soft repression" involving the use of social pressure against peers to get people to stop doing undesirable things. In short, the Chinese state is using a repertoire of activities against a particular subset of the population but the unasked question remains: is this repertoire similar to/different from others in the Chinese state? Is the repertoire changing over time? With the focus on Shuitou, is the repertoire in this particular part of China different from the rest and, if so, why? Again, no clue to these questions are offered.

The perils of not citing the social science literature are discovered in other ways as well. For example, consideration of my "tyrannical peace" article would have sensitized the author to the fact that a government with a single party is less likely to employ the most aggressive and vicious forms of repression as it is more likely to try and channel activities into the pre-existing party apparatus. This works well with the cultural pressure exerted within Chinese society. This type of society is also more likely to try and employ the rhetoric of democratic governance in many respects as it attempts to deal with justify its action. At the same time, these governments (like democracies) are more likely to engage in repressive activity when they feel threatened which they are intricately connected with identifying/classifying. Chinese concerns with xenophobia and communist persecution (also not discussed in the article) are very important here. This provides a constantly available source of repressive justification.

Additionally, reference to the literature would have helped the author better understand the move underground in repressive contexts that often is found. It would also have helped them understand the existence of churches as "abeyance" structures (i.e., a go-to place for individuals who are challenging political authorities but who are not yet able to be overt in their efforts). Indeed, it was interesting that the author wanted to tell a more hopeful story but they were only able to hang their hat on the generational rift that seemed to exist between the older individuals who stayed in church on the appointed days of worship and were accepting the cross removal and the younger individuals who stayed in church but on a different day of worship who appeared to be less accepting. The church provided a space for both but the meanings of that space seemed to vary - or, did it. Again, we are left with no clue by the author.

Now, clearly I am not expecting the author to write an academic article. Who would want to read that on a beautiful Sunday or Monday? Rather, I am suggesting that the article might have been a bit better had they employed some of the existing scholarship to frame their discussion and guide their effort. Such an orientation would have prompted them to ask some interesting questions. It may have also decreased the Chineseness of the piece and prompted them as well as the reader to consider what other cases this was similar to. Many countries have persecuted religions, why not discuss some of them? Are cross removals unique to China? What has happened when these activities were undertaken in the past? Why is India's approach to dealing with religions that challenge the state so different from China?

I suppose that Daniel Borstin and James Carse would be happy about this piece as the author of the article prompted me to ask a variety of questions which continued the conversation in a way. That said, i could think of other ways that I might have spent my Sunday and Monday rather than railing against the current practices of journalistic accidental tourism into the topic of conflict and contentious politics.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed