The difference in approach here should sound familiar to those aware of repression research. For a while now scholars have been differentiating between what they call "indiscriminate" and "selective" targeting. The former concerns where state perpetrators do not care about who they go after. The latter concerns where state perpetrators care a great deal. Later work highlighted another tactical selection: "collective". This is where state perpetrators concern themselves with only going after certain people but within that category they really do not care who they get (i.e., old, young, political or apolitical).

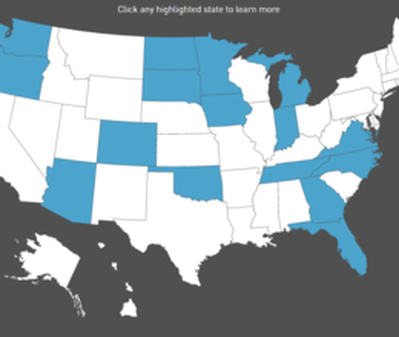

The differences in targeting are relevant to the current discussion of ICE targeting because researchers have identified that if targeting can be made to be more selective, then non-targeted individuals are less likely to care. This allowed President Obama to escape negative attention on this point (at least that which got raised up to a very large criticism) because he was going after individuals that had few supporters and a relatively underdeveloped network. In contrast, President Trump is largely sending ICE agents out in a manner that looks more indiscriminate in nature but targeted against a specific community. This is classified as collective targeting. Now, indiscriminate behavior is believed to be problematic to governments because it sends those potentially subject to it against political authorities and into the arms of the opponents. Collective behavior is not as likely to have this impact because the targets can still be portrayed as the other.

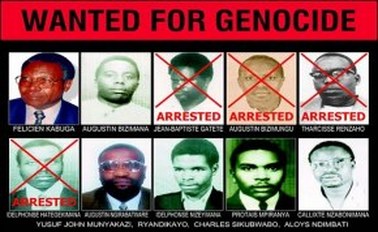

This is just where things get interesting though from an anti-repression stance. The degree to which the targets can be made to look just like other Americans: de-otherizing as it were, then support for the policy will be diminished and folks will rise up against the use of state coercion/force. Consequently, keep a look out for the stories about ICE arrests and always, always, always look for the framing. For example, the image above shows the target with their back to you. There is no discussion of context. There is no discussion of what their life was like before they got got. They just look like a criminal. In contrast, one could have the photo taken of the target looking at you - compelling you to consider their humanity, their americanness and their worth. One could have a photo taken on their empty chair, empty family or empty neighborhood - post extraction. In line with my Rashomon argument, I am sure that the direction varies with the ideological orientation of the source or, at least, it should.

First they came for the immigrants and i did not speak up because i was an immigrant...

Caveat Civis people

RSS Feed

RSS Feed